- Home

- Constance Leeds

The Silver Cup

The Silver Cup Read online

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Title Page

Dedication

FALL

Chapter 1 - THE SILVERSMITH

Chapter 2 - TRADING

Chapter 3 - AGNES

Chapter 4 - A DEEPER SOUND

Chapter 5 - FIRST FROST

Chapter 6 - BLOODY NOVEMBER

Chapter 7 - THE WOODS

WINTER

Chapter 8 - CHRISTMAS

Chapter 9 - COLD WINTER TALES

Chapter 10 - BAD FEET, BAD TIMES

Chapter 11 - NOBLE COUSINS

SPRING

Chapter 12 - SMUDGE

Chapter 13 - HERRING AND EELS

Chapter 14 - EASTER

Chapter 15 - THE DISAPPEARANCE

Chapter 16 - ALONE

Chapter 17 - HAGAN OF WORMS

Chapter 18 - HAGAN’S ACCOUNT

Chapter 19 - THE GIRL

Chapter 21 - SILENCE

SUMMER

Chapter 22 - LEAH

Chapter 23 - UNDERSTANDING

Chapter 24 - LEAH’S STORY

Chapter 25 - FLIES AND CURSES

Chapter 26 - SUMMERTIME

Chapter 27 - HEALING

Chapter 28 - A PLAN

Chapter 29 - A PILGRIMAGE

Chapter 30 - THE RETURN

Chapter 31 - SEASONS OF CHANGE

Chapter 32 - AN ENDING

AUTHOR’S NOTE

HISTORICAL NOTE

GLOSSARY

FOREIGN PHRASES

IT’S THE YEAR 1095, and fifteen-year-old Anna longs for a different life in her small German village. But as the seasons turn, the year proves anything but ordinary.

Her youngest cousin, Thomas, disappears, and Anna suspects his mother of an unspeakable crime. Another cousin, Martin, runs away to join a renegade army of Crusaders, who bring murder and destruction to Jews in the nearby city of Worms.

When Anna risks everything to rescue Leah, an orphaned Jewish girl whose only connection to her family is a silver cup, the two girls forge a remarkable friendship that defies the intolerance of their time.

Filling her story with fascinating period details, debut novelist Constance Leeds paints a rich, colorful picture of an eleventh-century life marked by courage, will, and most of all—hope.

Constance Leeds is a retired lawyer and the mother of three grown children with whom she once operated a less than profitable poultry farm. She lives on the banks of the Charles River, near Boston, Massachusetts. Research for this story took her to the banks of the Rhine, to the cities of Worms and Strasbourg.

The author considered dedicating this book to her devoted corgis, Puck and George Eliot, but she did not. Visit the author at www.constanceleeds.com

The Silver Cup

Constance Leeds

eISBN : 978-0-670-06157-0

Ages: 12 up

Grades: 7 up

Pages: 224

Trim size: 5½ x 8¼

On Sale: April 5, 2007

Rights: World

Price: $16.99 / (CAN $21.00)

Text copyright © Constance Leeds, 2007

All rights reserved.

http://us.penguingroup.com

For Billy, now and always

(With love to Lauriston, Corey, and Will)

FALL

1

THE SILVERSMITH

September 20, 1095

Anna blinked, closed her eyes tightly, and drew the coarse cloth over her face. She turned toward the wall, until her father tapped her shoulder again.

“Anna.”

She rolled back and unfolded herself from the covers.

“Anna.”

“Is it morning, Father?”

“Almost.”

“Is something wrong?”

“No. I want an early start for Worms. It’s market day. Would you like to come?”

“Oh, yes!” said Anna, rubbing her eyes and springing from the bed.

In an instant, she had pulled on her green homespun kirtle and fastened her belt. Meanwhile, her cousin Martin stretched, yawned, and slowly rolled to his feet, reluctant to surrender the wide bed he shared with his uncle and his cousin Anna. Martin shook his head of blond curls and muttered to himself about the unfairness of his day.

Anna hummed as she ladled ale into cups of horn. She served her father and Martin chunks of bread to dip in a bowl of buttermilk, and they sat on three stools gathered in the narrow pool of light that streamed through the open door.

“Why isn’t Martin going to Worms today? ” asked Anna, delighted by the prospect of a journey.

“Your cousin is helping his brothers today. I have tools to deliver, and we need more salt. We’ll leave shortly.”

“Lucky Anna! A trip to the city while I haul sacks of flour. You’ll have an easy day, so you won’t need this,” said Martin as he swiped Anna’s portion of bread and jammed it in his mouth.

Anna didn’t care; for once, she would be the one going to the city. It was her sixteenth fall, but she had been to Worms, a cathedral city on the near bank of the Rhine River, only a handful of times. Though Martin was six months younger, he had traveled to Worms countless times helping her father, Gunther. Anna was feeling almost smug as they bid farewell to Martin, who spewed bread particles when he attempted to reply with his overstuffed mouth.

The cool fields smoked in the warm morning sunlight, and the horse, with its two riders, plodded steadily along the busy road. There were very few horses in her village and none so grand as Gunther’s large black mare. Anna felt very proud, seated behind him. Gunther carried a small package of ash-handled hammers, delicate chisels, and a tiny anvil. Anna had laughed when she had seen the tools.

“Has Uncle Karl become the blacksmith for a dwarf ? ”

“For a silversmith.”

The horse splashed across a stream whose clear water moved quickly southward to the wide, north-flowing Rhine River and the city of Worms. Dust from the dry road coated Anna’s dampened shoes as the path ribboned through rich green fields and along hillsides dotted with vineyards. Deep woods ringed the cultivated fields. Ageless and untamed, the forest was both necessary and terrifying to the sixty German households in her town, huddled within a wooden palisade that served as both boundary and protection. For most of Anna’s neighbors, this town was all the world that they needed or even wanted to know.

On a rise that overlooked the town and countryside was the marlstone wall of the manor house where Gunther was born. Though the manor was now the home of his half brother, Anna had never been inside because when her father married her mother, a blacksmith’s daughter, his noble family had recognized neither the marriage nor, thereafter, Gunther.

Passing through the fields, Gunther greeted fellow townspeople with a wordless nod. Beyond memory, Anna’s mother’s people had been smiths in the town, and always freemen. But their iron ore came from pits in the manor’s marshes and the charcoal came from the manor’s timber. Most of the rich fields belonged to the manor, and many of Anna’s neighbors owed rents or service to Gunther’s brother. Although Gunther had come to live among them, to his neighbors he remained the brother of the lord. His noble birth and rumors of his expert swordsmanship set Gunther apart, a man to be respected but not embraced.

By late morning they arrived at the city wall.

This is how Martin spends his days. I would never complain , thought Anna happily as they entered by the western city gate into Worms and dismounted.

Anna was delighted by the bustle, and she craned about, looking at the wooden houses crowded along dirt streets. In the square below the massive maroon stone Cathedral of Saint Peter, craftsmen and farmers had gathered to sell their goods

in a clutter of carts and wagons and stalls. It was harvest season, and the marketplace was crammed with the bounty of the countryside. Anna had to hop over a squawking brown hen whose legs were tied together. Gunther pointed out a dishonest fishmonger who had brightened his spoiled fish with a pig’s red blood. Nearby scrawny dogs growled over garbage, while children played tag through the stalls. A group of men clamored over a game of dice. The dice were made of bone and clinked on the hard-packed earth, while the men jostled and wagered and cursed each roll.

“The silversmith is north, beyond the marketplace,” said Gunther, jabbing Anna’s shoulder. “Don’t stare.”

Her head down, Anna followed her father, who led the horse over the hill, toward Saint Peter’s, and then beyond and downhill toward the river. The streets were shadowed and busy, and several groups of men milled about and talked loudly, using strange words and cadences that Anna did not recognize.

“Father, these people are speaking gibberish. Where are we? ”

“The Jewish Quarter. Most of the Jews live here, on the north side of the city, near the Martinstor. Not far from the Church of Saint Martin.”

“Can you understand them, Father? ”

Gunther shook his head and said, “The Jews speak their own language.”

“Can’t they speak our language? ”

“Yes, Anna. As well as you or I. Enough questions.”

“Martin says they are the devil’s people.”

“Nonsense. Come,” said Gunther, and he walked briskly ahead of Anna.

When they reached a street with broad, strong houses, they stopped at the third doorway, and Gunther knocked. The door to the silversmith’s was opened by a smiling boy in a clean leather apron. He nodded to Gunther.

“Ah, welcome, sir. My father will be delighted to see you. I’ll take your horse to the back and water her.”

“Thank you,” said Gunther, nudging Anna as they stepped inside.

The narrow hall funneled into a wide back room, bright with sunlight from the generous window along its back wall. A large stone hearth with a small forge warmed the high space, and Anna was struck by the quiet and the light. It was nothing like her uncle Karl’s iron forge, but she was also uneasy, remembering her cousin Martin’s stories of Jews with black magic and evil eyes.

At a bench near the window, a hunched man scratched away at the surface of a small cup which had been bent and hammered around a polished hardwood mold. Black dust floated from his small file, and a pile of shavings grew beneath the cup. Behind the silversmith stood a heavy man and three children: two boys and a girl. The silversmith looked up from his work.

“I am glad to see you, Gunther. You have my tools? ”

“Yes, Samuel,” answered Gunther as he placed the bundle on the bench.

The silversmith gestured with his chin at Anna and asked, “Who is this maid? ”

“My daughter, Anna.”

Samuel nodded politely to Anna and asked Gunther, “And where is your boy with the yellow hair? ”

“My nephew Martin? He’s elsewhere today.”

“I see. Can you wait? I am just finishing the niello on this cup for a very special customer.” He indicated the taller boy, who grinned.

The craftsman’s file scraped along the cup’s surface making a grating, unpleasant noise. Gunther and Anna moved to a bench, which the boy in the apron had set away from the smoke but near the warmth of the fire. Anna stared at the family, who in turn watched the silversmith as he began to rub the surface of the cup with pumice and then with a soft leather cloth. The silver brightened with each rub, and the craftsman chatted with his customers. Anna understood little as she watched the girl, who looked close to her own age, talking with her hands fluttering, poking the boys and causing everyone, even the silversmith and his son, to smile and laugh. Now and then Anna thought she caught a word from her own language, but she had no idea what they were talking and laughing about. Are they mocking me, Anna wondered.The girl was so pretty, and Anna had never seen a more elegant dress. Its wool was the color of the Rhine at day’s end—deep blue green. The sleeves were dark blue, laced from the wrists to the elbows with a thick fir-green ribbon. More of the same ribbon circled her waist several times. Anna folded her hands over a patch on her kirtle.

Anna looked up and found the girl watching her, and when their eyes met, the girl smiled brightly. But Anna dropped her eyes and moved closer to her father. The girl became silent, and the laughter stopped.

2

TRADING

September 20, 1095

Anna studied her feet as the silversmith promised to deliver the cup the next day, and the heavy man and his children departed.

“Sorry you had to wait, Gunther. Jakob is a very important man. And the cup is to celebrate his son’s bar mitzvah when he becomes a man in the synagogue.” Samuel held the cup high, catching the sunlight on the bright, polished surface, and said, “L’chaim! ”

Alarmed by Samuel’s foreign incantation, Anna grabbed her father’s sleeve, but he moved away from her and went to the bench where Samuel worked. As Gunther unwrapped each tool, the silversmith examined it carefully, clicking his tongue and whistling softly.

“Dos gefelt mir. Ah, they are perfect. Feel the balance of this hammer, mayn zundele.”

The boy took the hammer. Anna watched her father. She had never been in a Jewish home; she was frightened by their strange language and longed to leave. She fidgeted as her father bargained with the silversmith, trading the tools for salt and vinegar. Then Samuel handed Gunther a small wooden box.

“Spices from the fat man,” said Samuel.

“Fat man?” asked Gunther.

“Alevei! We would be lucky to eat at his table, right, mayn zundele? ” The silversmith smiled at his son who nodded. “Yes, the man who just left, Jakob. He’s a very rich merchant from across the way.”

“Yes?”

“He wants three small knife blades. I’ll make silver handles,” said Samuel.

“Plain blades?” asked Gunther.

“I hear your smith etches with great skill. Nu, let him decorate the blades. Two with oak leaves and acorns. The other with morning glories. The finest he can make.”

“A generous fee,” said Gunt her opening the box. “In a few weeks then, I will return with the blades for Jakob.”

After they left the silversmith, Anna asked her father, “Must you trade with those people?”

“I am eager to trade with them.”

“Martin says the Jews are wicked.”

“Your cousin is a story teller,” said Gunther curtly.

“You aren’t afraid? ”asked Anna.

Gunther frowned, and Anna thought, He’ll never ever bring me to the city again. She followed her father back to the marketplace, where he traded four nails for two meat pies for their meal and some honey cakes for later. More nails went to a butcher who handed Gunther a sack of animal horns. An ax head was traded for a fine pair of leather shoes for Elisabeth, one of Anna’s cousins.

By mid-afternoon they were on the road, and before sundown, Anna and her father were home. The September evening was warm, so they sat on stools in the garden. Anna darned a stocking in the last of the daylight while Gunther sat with his back against the wall of the house, sipping ale.

“I’ve had a hard day!” said Martin, returning from his father’s house. “I’d be too tired to lift a spoon.”

His face was smudged, and his hair, usually a halo of yellow curls, was dark and stringy and sticking to his forehead.

“Poor Martin!” said Anna gleefully. “You probably won’t want this honey cake we got for you in Worms.”

“This needs no spoon,” said Martin snatching the cake and dropping to the ground with a sigh. He stretched his legs and wiggled his toes as he sat at Gunther’s feet. “I could use some ale, Anna.”

“Of course, my lord,” said Anna with a grand curtsy. She was delighted to see that, for once, Martin’s day had been harder than hers. �

�Wait until you hear about Worms.” Anna brought Martin a mug and began to tell him about the silversmith and about the girl in the beautiful dress.

“You didn’t go too close, Anna? ” asked Martin, licking each of his sticky fingers.

“No, I—”

“Good. We dealt with a Jew in Worms last month. With my own eyes, I saw that, in truth, he was no man,” said Martin.

“What do you mean? ”

“He seemed nice enough, but just as he turned away from us, I saw a tail, a long skinny rat tail, slip from beneath his black cloak. He knew I saw it and quickly tucked it in, winking at me with his evil eye. My skin began to prickle, and I could smell brimstone—”

“Martin, you saw nothing of the kind!” said Gunther setting down his ale. “I’ve traded with Samuel many times. Anna has just seen the very same man. The Jews are a separate people, but they are people. They keep to themselves, but they travel far and wide, and their people are scattered throughout the lands. They trade with each other across mountains and seas. Far beyond the river. Places a simple German boy like you shall never see.”

Places I’ll certainly never see either, thought Anna wistfully as she looked out into the garden. She noticed the first pale pears in the branches of her favorite tree, and she remembered sitting in its shade with her mother before she died. Her mother would tell Anna how she had fallen in love with Gunther and how he, the second son of a knight, had fallen in love with a smith’s daughter. He had given up everything for Anna’s mother.

“Your father’s mother died giving birth to him, and his father never forgave him. No one loved him until he met me. And I loved him more than anything. More than the spring,” her mother had said.

Anna knew that her father as the son in a noble family had never learned a craft, but he had made himself useful trading the iron goods that his bride’s family produced. The forge made sickles, knives, axes, and swords, and Gunther traveled to the nearby towns and manors along the river and traded them for livestock, salt, leather, cheese, fish, wine, and woolen cloth. Trade was good, and Gunther built a separate house on the far side of the garden, where he lived with his wife and their daughter, Anna.

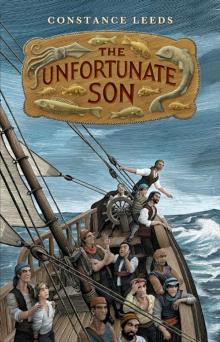

The Unfortunate Son

The Unfortunate Son The Silver Cup

The Silver Cup