- Home

- Constance Leeds

The Silver Cup Page 8

The Silver Cup Read online

Page 8

“Do you miss Martin? ” she asked her father.

Gunther nodded, and looking at the fur bundle curved happily against his daughter, he added, “I don’t think your dog misses him.”

“No, Smudge didn’t trust Martin. But it’s so quiet without him.”

“Too quiet. I need Martin in my work.”

“What will you do, Father?”

“I don’t know. I need his strong back, and his help to watch my goods. I depended on his excellent memory for people and places. He remembered roads. If we were separated, he could always find his way back to me.”

“And he made friends so easily.”

“Too easily perhaps.”

“Will you go alone?”

“I can wait only a bit longer for his return. Then I’ll have to go. I suppose I should look for a new boy to help.”

“Not Dieter.”

“No, certainly not that one,” agreed Gunther. “Martin will be difficult to replace.”

“Each day, I hope I’ll look up and see Martin filling the doorway.”

“I, too. But Anna, there are troubling rumors about the army of Emich. I’ve heard that he traveled south from Cologne to Speyer on this side of the River. That may be where Martin sought to join him.”

“Hasn’t Martin traveled there with you many times?”

Gunther nodded. “Martin knows Speyer. There are reports of mischief and much worse. They say Emich and his army attacked and murdered some Jews in Speyer. Then they moved on, north along the river, not east toward the Holy Land. I fear the count intends to wage his war along our side of the river.”

“I’ll pray Martin is not among this Emich’s followers.”

“I don’t like the stories I am hearing. Perhaps Martin will see that this hero is not doing the work of the Lord.”

Anna said hopefully, “Then he’ll come home.”

17

HAGAN OF WORMS

May 21, 1096

The earth was dew covered, and when she opened the door to begin her day, Anna shivered in the fog of a dull morning. She noticed how slowly and stiffly her father rose and dressed. He shuffled from the house to the privy without looking up from his feet, and when he returned, he drew his stool close to the fire that Anna had stoked, and warmed his hands. Anna gave him some cheese and a flat wheat-meal cake.

“You slept poorly, Father.”

“I have too much to think about. I wish Martin were here.”

“I know,” said Anna.

“Today I must go to Worms, to Samuel, the silversmith. Come with me. There is a market today, and we might learn something of this Emich’s whereabouts.”

“Do you think they might be in Worms? ”

“I don’t know, but in any event, there’s something there I want to show you. We’ll be back well before dark.”

Anna thought about the fall when she last went to Worms. How much had changed since then! Now, both Thomas and Martin were gone. She had no hope that she would see Thomas again, but Anna prayed they would find Martin. She fetched the water and mixed some grain and milk for Smudge. Then she braided her hair with care, tying it with the green ribbon Martin had given her. She looked at her tall father, who was fastening a broad leather belt below his waist. He was still handsome and strong, with sandy hair cut blunt across his neck. His eyes were amber, and his skin was tanned and creased from his days on the road. She loved him very much, but the house was bitterly silent without her cousin.

The horse with its two riders clopped along briskly toward the east. As the sun burned through the mist, the day turned fine and summery. Yet, they met only a handful of travelers, all hurrying away from Worms.

“You’d think we had set out ahead of the world this morning,” said Gunther.

“Yes, we almost have the road to ourselves.”

“Unusual. I wonder if there is a cause? Surely not the weather. The sky is clearing. The day will be bright.”

“Father, what’s that below us? ” asked Anna, pointing to a yellow haze on the road below.

“I don’t know. Worms is just beyond.”

As they neared the city, Anna realized that the haze was smoke; the air was sour, and the city was clouded, cloaked as they approached. She turned and looked over her shoulder. Toward home, the sky had cleared to blue, but not over Worms. With each step, the smell deepened. Not wood smoke, but sweet and then horrible. Blood smoke. The horse began to snort and hesitate. Anna’s father reined the mare firmly and urged her along.

They arrived at Worms by the southwest gate, the Andrestor, near the Church of Saint Andreas. The gate was open, and they passed within and dismounted. Gunther calmed the horse, stroking her nose and whispering to the uneasy animal.

“Strange,” he said. “I have never seen the Andrestor unattended. We’ll leave the horse with Hagan, a fish seller I trust. His house is down the way from this gate. He knows Martin. Perhaps he has even seen him.”

“I hope so,” said Anna. “Something has happened here.”

“Yes, but what?”

They spoke no more as they passed along the narrow street where every door was closed, every window shuttered. The quiet rang in their ears. Gunther knocked at the door of a solid, tidy house.

“The iron merchant, Gunther. What brings you here with such a fair maid? You’ve come to my city at a very bad time,” said the fat, many-chinned man who opened the door.

“Hagan, this is my daughter Anna.”

Hagan licked his teeth and began to work a toothpick between them as he studied Anna’s face. He turned to Gunther and said, “A fine-looking girl. I wish you had brought her on another morning.”

“Will you mind the horse for me? I have business to attend, and we hope to find news of my nephew.”

“Yes, of course. But your nephew? Martin, the boy who plays the pipe? Where’s he gone? ”

“We believe he may have joined the army of a count from Leiningen, Count Emich.”

“I hope you’re wrong, Gunther,” said Hagan, frowning.

“Why? Do you know of this Emich? ”

“Everyone in Worms knows Emich now.”

“Has he been here? ”

“Thank Emich for the smoke-filled sky. And thank the Lord that my city did not burn to the ground,” answered Hagan. “Come inside, Gunther. Let me give you both some drink, and I’ll tell you about Count Emich. And you can pray with me that your Martin is not among his men.”

“We must be quick. I have business in the market,” said Gunther as he and Anna followed Hagan inside.

The house smelled of the sea and decay as they threaded between baskets of salted herring and barrels of all sizes. Strings of yellowed, dried codfish hung from the ceiling, and Gunther had to duck often. Peering into a giant barrel filled with water, Anna saw two large fish swimming very slowly.

“You won’t find any business in this city today,” said Hagan. “Come. Sit. You will need the rest if you want to look for the boy. The count and his men have moved on, but only yesterday. Perhaps you will find someone to help you. Martin is well known here and well liked. Come, rest first, and let me tell you what I know.”

18

HAGAN’S ACCOUNT

May 21, 1096

Hagan pulled a bench into the light from an open door, so that they looked out onto a small garden behind his house. Anna watched Hagan’s son tether the horse in the leafy shade of a beech tree and fetch water for the animal.

“My only son,” said Hagan, pointing to the boy. “He’s a good boy. Not as clever as your Martin. But a good boy. To begin, do you know much about Count Emich? ”

“I’ve heard that he claims to be a general chosen by heaven,” said Gunther.

“Emperor. He claims he is the emperor of the apocalypse.”

“Martin was taken with the tales. Of late, I have heard Emich caused some mischief in Speyer,” said Gunther.

“Mischief ? ” Hagan shook his head. “Speyer isn’t so different from Worms. It, too,

is a city with a bishop. Different, though. The bishop in Speyer had a particular affection for the Jewish race as did the bishop before him, but Speyer had few of that race until its earlier bishop built a small walled town, a separate town outside the city’s own walls, and he invited Jews from throughout the land to live in this separate place with the Church’s protection, yet under their own rules. Many came, and each year the Jews paid the Bishop silver. So, for years the Jews of Speyer lived untroubled behind their own walls.”

Hagan ladled ale into a dark blue mug for Anna and Gunther to share. The ale was mild and nutty, and Anna realized that she was thirsty from the sour air of the city and the dankness of Hagan’s house.

Hagan continued. “So the Jews prospered, and the bishop grew rich from their silver. Then Emich’s army entered Speyer some days ago. They say Emich pointed to the Jews and claimed that these were the very people who had killed our lord Jesus. Emich demanded silver and insisted on their conversion, but he allowed no time for either. His impatience led to robbery and looting and murder. Speyer’s bishop was enraged and moved to save his valuable Jews.”

“How? ” asked Anna.

“He gathered the Jews into his castle, and all but a dozen were saved from Emich’s mob, which by then included many of the town’s people. Some of Emich’s men were even punished.”

“I heard nothing of that,” said Gunther.

“The bishop cut off the hands of some of Emich soldiers,” said Hagan with a swift chop of his fleshy hand.

Anna gasped, and he continued.

“But that was Speyer. Here in Worms we have always had even more of that foreign race. Not behind a wall as in Speyer, but mostly together in the north quarter, near the Martinstor. Haven’t you traded with them?”

Gunther nodded and said, “Yes, I trade with a few.”

“We’re here to see a Jewish silversmith,” said Anna.

“The Jews bought my fish, and they paid well. No more, Gunther. On Sunday, this count you seek arrived at our city with a mob beyond counting.” Hagan stopped for a moment and closed his eyes. “Like a school of bluefish. Frenzied feeding bluefish. Have you ever seen those ocean fish when they feed?”

“No,” answered Gunther.

“Ah, a terrifying sight. Well, these weren’t soldiers but an angry, hungry mass, schooling through our streets, looking for any food or drink or loot. My town’s people have little enough to feed themselves. So there we were with this boiling throng out for Jewish plunder and blood.” He rubbed his eyes with his thick palms.

Hagan’s tale was making Anna more and more uneasy, and as she listened, she turned the blue mug in her hands, examining the fish design along its rim.

“Emich’s men were joined by my neighbors, and together, they ripped apart the Jewish neighborhood. Old men with canes, women with babies still at the breast. Everyone robbed, beaten, stabbed. Slaughtered. Isn’t this too horrifying for your daughter’s ears?” said Hagan turning to Gunther.

“Anna, go wait in the garden.”

“No. Please, Father.”

“Perhaps we should go now,” said Gunther.

“Wait, there’s more,” said Hagan. “In the square near the Martinstor, I saw, with my own eyes, two Jewish girls, younger than your Anna, raped over and over, and then beheaded while people laughed. I saw young children pierced through with swords and flung into the streets like sacks of grain. Men and women bloodied, screaming, praying to their god. The streets filled with bodies, and the mob fell upon the dead, stealing every possession, every shred.”

Hagan stood and walked to the doorway, and leaning against the jamb he continued, with his wide back to Anna and Gunther, who had risen to leave but still listened.

“Everything was taken, stolen. Houses were pulled apart, and their synagogue was torched. It smelled like hell itself. Who could imagine that yesterday could be worse still?”

“What happened yesterday?” asked Anna, afraid to hear.

“Yesterday? Yesterday, they defiled the cathedral close. Any Jews who escaped fled to Saint Peter’s to ask our bishop for protection. He said he would save them if they accepted baptism. The stiff-necked Jews refused, and the mob stormed the bishop’s house. St. Peter’s echoed with the howling. Every Jew was killed, killed and stripped. So there we are. Today is Wednesday? For three days your Emich raged, a storm of hate and death in Worms. Today you will find calm. The storm moved north I hear, and my city is fouled and unholy. Go home. If Martin is with this mob, leave him to his fate.”

Anna struggled to absorb what Hagan was saying, but it was too horrible. Martin could never do such things, she thought. Then she remembered how he had always spoken of Jews. Or could he?

“Father, please! We must find Martin.”

“I must. You stay here, Anna. I’ll return for you as soon as I’ve delivered the swords.”

“Don’t leave me here. Let me stay with you.” Anna began to cry.

Gunther looked down at his daughter, drew his hand slowly across his mouth, and hesitated. Hagan raised his brow and leaned toward Anna. “You’ll need some cloth to cover your mouth. My city is a reeking pyre.”

Gunther reached into his sleeve and handed Anna a piece of woolen cloth he carried to cover his mouth when the road was dusty. It smelled of him, and Anna was grateful.

19

THE GIRL

May 21, 1096

Anna and Gunther trudged uphill through the deserted city toward the towers of the Cathedral of Saint Peter and the marketplace. As they passed a well, Anna remembered that Hagan had said there had been a rumor that the well water had been poisoned. Emich had claimed that the city’s Jews boiled a man alive. By pouring that tainted water into the city’s wells, the Jews had hoped to sicken Emich’s army. Hearing the story, the mob began shouting, “Death to the Christ killers” and then Emich declared, “No one shall fight with me until he has killed a Jew.”

Anna held the woolen cloth to her nose, but as they climbed the cathedral’s hill, the stench grew until the smell of smoke and worse slammed into them, and they had to stop. Nothing prepared them for what they saw in front of St. Peter’s. Father and daughter fell to their knees and vomited. They retched until each was emptied of everything. Anna’s chest ached, and her throat burned, and she began to shake. She felt cold, cold though the day had brightened to a summer morning.

She had to look. Shirtless men were hauling naked bodies from the cathedral and heaving them onto carts. These were people, not some vicious race of monsters, not goats nor devils with tails. People. So many people. Men and women, fat and thin, children, babies—all naked and bloodied like butchered animals flung into piles on the street, into the carts, with no care. Below, at the back side of the hill, an unholy pyre roared and consumed some of the dead. Dogs and crows picked at the piles of bodies waiting for the carters . And everywhere, there were flies.

Anna shivered, and her father clutched her to him. She felt him shudder, and she began to cry. They stumbled downhill from the cathedral, along the edge of the deserted marketplace and sat on some casks that were stacked on the far side. Anna was empty, wrung, and her eyes stung from the smoke and from crying. She gulped down mouthfuls of air and felt as cold as January. After a while, Gunther handed her some bread from home and some ale he had carried in his flagon. She had no appetite, but he insisted. Anna nibbled at the bread.

“Anna, I would leave, but I have these swords for the silversmith.”

Gunther looked around and added, “Perhaps he’s fled. I fear Samuel needed them a few days ago. You should have stayed with Hagan.”

Anna shrugged. Her head was filled with sounds but no words. Gunther patted the swords in the packet slung over his shoulder and shook his head. Anna saw that he was unsure.

“I should try,” he said.

They walked north to what remained of the Jewish quarter. Burned and destroyed, very few houses stood. All was quiet except for the snap of ebbing fires and the crack of wood settling.

<

br /> “It’s gone. Everything, everyone,” said Gunther as he turned in a slow circle.

All that remained of the silversmith’s house was the hearth and a part of the back wall where the window had been. Anna looked about, gazing across at discarded, broken crates and casks.

Then Anna saw her. She was crouched behind the rubble, squeezed against the remains of a wall.

Anna turned and said softly, “Father, there’s a girl hiding behind that wall.”

“I wouldn’t doubt that,” said Gunther. “This city has always been plagued with starving scavengers. Magpies who steal bits and scraps.”

“I didn’t finish my bread. I’ll give it to her.”

“She may be diseased or mad, and she’ll surely have lice. Just throw the bread, and let’s leave this monstrous place.”

Anna meant to obey, but as she approached, she heard muffled sobs. Not the sound of madness, but of such grief that she did not throw the bread. Instead, she began to push aside the rubble. The girl’s face was not visible for she had balled herself tightly, clutching her knees against her chest.

But she was not dressed like a beggar. Her shoes, though stained, were of soft buff leather and fine, and her dress was of elegant cloth and dyed a honey color Anna had never seen before. This was no child of the street.

Anna spoke gently, but the trembling girl did not look up. When Anna tried to draw her out, Gunther hastened to pull Anna away. He, too, was surprised by the dress.

“She must be a Jew’s child. Save your bread. She won’t take it. There’s no helping those people. Let’s be gone. Hagan was right. There’s nothing for us here.”

“But the girl?”

“What can we do? Come, let’s go.”

The girl raised her eyes, and Anna saw her face. It was the girl from the silversmith’s.

“I know you!” said Anna.

The girl put her head down and rocked.

Anna tapped her shoulder gently, “Where is your father? Do you know where your father and your brothers are? ”

The girl did not reply.

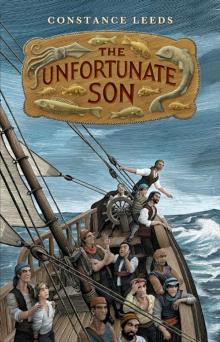

The Unfortunate Son

The Unfortunate Son The Silver Cup

The Silver Cup